Alternate Unconscious: Uznadze’s Theory of Set

This article is also available in video format.

Table of Contents

Abstract

In the following work I briefly explore the general psychology of set – a field founded by Georgian psychologist Dimitri Uznadze who rigorously, through experimental methods offered an alternate understanding of the unconscious, in contrast to fields such as psychoanalysis. The set is understood as a general state of readiness that constitutes purposive behavior. The issue of terminology is explored, as well as the usage of terms such as “set” and “attitude” in fragmentary studies that explored the same phenomenon, but lacked the unified approach, which is one of the merits of set psychology, explaining human functioning as a whole. This merit becomes evident by exploring Charpentier’s Illusion. The factors of set formation are discussed that serve the foundation of purposive behavior. Two types of sets are distinguished in terms of their differentiated and fixed nature. Their nature is further elaborated upon discussing their interrelationship. This is followed by exploring the notion of two levels of psychic activity which is based on Uznadze’s understanding of the term “objectification” and which is integral to understanding the psychology of set as a field of general psychology.

1 Introduction

In 1979 the second international symposium was conducted in Tbilisi, Georgia, where psychologists all around the world gathered to share their findings about one of the most ellusive phenomena known to the field: the unconscious. 150 guests from 17 countries attended (not including hosts from Soviet Union) and considering the fact that the “Iron Curtain” was still holding strong in USSR, these numbers were quite immense (Imedadze, 2022).

There were two notable things regarding this event, at least in the scope of this work. Firstly, in the first symposium of the unconscious held in Boston in 1910, what unified all the psychologists gathered there was their disregard for the Freud’s understanding of the unconscious. Unsurprisingly, Freud and his followers were not invited. At the Tbilisi symposium, however, representatives of many different psychoanalytic fields were attending. Even Jacques Lacan was invited, who unfortunately could not attend (Angelini, 2008). Considering the fact that in USSR psychoanalysis was the “scarecrow” of psychology, this was a notable event indeed. Secondly, the only opponent that psychoanalysis had in that symposium, as a general theory that explicitly focused on the unconscious, was Dimitri Uznadze’s Georgian school, psychology of set which, in spite of taking a completely different approach from psychoanalytic thought and practice, was viewed as the alternate theory of unconscious that the USSR had to offer in competition with its western peers. It was thanks to T. Bassin, who saw the value of Uznadze’s school, that the symposium was held in Tbilisi as he was one of the initiators of this event, alongside A. Sherozia and A. Prangishvili. Nevertheless, It took a great amount of effort for Uznadze and his colleagues to gain recognition which, in the end, payed off (Imedadze, 2022).

What greatly distinguishes the methodology of Uznadze’s school from psychoanalysis is the experimental approach to studying the unconscious. Although it made a name for itself after the Tbilisi symposium, its popularity outside post-soviet countries somehow has receded. Despite this, the theory of set offers a favorable approach for academic psychology which dismisses the achievements of psychoanalysis due to its allegedly unscientific methodology of exploring the unconscious.

2 Attitude or Set?

The terminology must be addressed first and foremost, namely the distinction between the attitude and set, and which one we should use when dealing with Uznadze’s notion. This will help us to formulate a general outline, which will serve as a guide throughout this work.

There doesn’t seem to be a concrete reason to draw strict conceptual distinctions between terms attitude and set, but we must nevertheless settle on one. Thus it would be helpful to see how each term is used in the literature available to us.

The original term in Georgian, used by Uznadze and his followers is “განწყობა” (pronounced gun-ts-ko-ba). In Georgian literature, both attitude and set can be translated into the same word and in Nadirashvili’s work named “განწყობის ფსიქოლოგია” (Nadirashvili, 1983), for example, All terms such as Allport’s attitude, Uznadze’s “განწყობა” and Muller’s (motor) set are all labeled as “განწყობა”. This is despite the fact that, as we will later see, motor set is restricted within the domain of physiology, while attitude carries a more general meaning and for Allport, more often than not, it is used in the context of social psychology. Uznadze’s notion, however, should be understood in the most general sense out of all three. Uznadze aimed to explain human functioning as a whole. This is not unlike Freud, who didn’t restrict his notion of the unconscious within the domain of psychopathology.

Other authors such as Nadareishvili (not to be confused with Nadirashvili) (see Nadareishvili, 2022; Nadareishvili & Chkheidze, 2013) and Imedadze (Imedadze, 2009, 2019, 2022) use the term set. The English translation of Uznadze’s fundamental work by Haigh (Uznadze & Haigh, 1966), which is virtually impossible to acquire in digital form, also uses the same term.

We will settle on using the term set, prominent in the most recent, but rather scarce English works in this field. This will prevent us from mistakingly attributing set in isolation to social psychology, which we might be prone to doing in the usage of attitude. At the same time, we should keep in mind that the phenomena maintains a psycho-physical nature, like a disposition of sorts, which is dynamic as it “sets” in motion the greater part of human activity.

Allport (1935) noted that H. Spencer was the first to put attitude under scientific investigation. Where he used the term “attitude of mind” to describe a position an individual assumes when dealing with opinions that are contradictory to one’s beliefs. Later, the first experimental work was conducted by Lange, where he studied reaction speed. There Lange concluded that a reaction speed to the stimulus is dependent, among other factors, on an inner psychological state which he called attitude. Studies on attitude ranged from explaining specific events restricted to something as specific as motor set (physical mobilization of force in muscles) to something as broad as a general state of readiness.

The issue of terminology, such as using different terms to describe the same phenomenon has been rather intricate and it will be addressed in chapter 4. For, now I will formulate a general definition that, upon reading the next chapters, can be dissected and understood in depth:

A set is a psycho-physical state of readiness that arises upon a specific coincidence of individual’s need with the situation and operational capacity and which determines his or her purposive behavior.

3 Defining Set Through Charpentier’s Illusion

In 1948, Uznadze showed the merits of his set theory by explaining the phenomenon called “Charpentier’s illusion” (see Murray, Ellis, Bandomir, & Ross, 1991), while also critically reviewing the existing theories surrounding the subject. Discussing where existing theories fell short and where Uznadze’s theory filled in the gaps, will help us formulate the most basic definition of set.

Charpentier’s illusion is described as follows: The objects of identical weight, but different sizes are perceived to have different weights. Muller and Schumann (1889, as cited in Nadirashvili, 1983) tried to explain the illusion with the concept of “motor set”. When a person intends to lift objects of different sizes, upon perceiving and visually assessing the objects, he automatically uses different impulses for each of them. For larger objects, a stronger impulse is mobilized, and for a smaller object – a weaker impulse. Since the objects weigh the same, a larger object lifted up with a stronger impulse leaves a sensation, as if it is “flying up in the air”. Accordingly, a smaller object of the same weight feels to be “sticking to the bottom”. Therefore the object that seems to be “flying up” feels lighter, while the object “sticking to the bottom” feels heavier.

To rule out the effect of “motor set”, Uznadze (2008) conducted experiments in different modalities of perception, where there would be no effects of “flying up” and “sticking to the bottom”. Baresthesiometer was used to apply pressure on subjects’ hands, so that they didn’t have to lift anything themselves. Initially, a pair of stimuli was applied to subjects multiple times: first strong, then weak. After multiple distributions of these pairs, participants were given a final pair of stimuli with equal pressures. It was discovered that they felt identical pressures to be different from one another. It was concluded, that the illusion appeared in many different modalities of perception, where it was possible to create sets that give rise to an illusionary perception of light, temperature, volume, etc. This means that the “motor set” doesn’t explain Charpentier’s illusion accurately (Nadirashvili, 1983).

Later, a notion of disappointed expectation was used by Martin and Muller (1899, as cited in Nadirashvili, 1983), According to which an additional factor was considered, namely the conscious expectation of a person that a perceived large object must be heavy, therefore upon lifting it, the weight in contrast to the expectation feels much lighter and the other way around for the lighter object.

If conscious expectation indeed played a role, then being aware of the effects of the illusion should disperse the effect. Strangely enough, experiments proved that removing the expectation factor, on the contrary, strengthened the illusionary effect (Nadirashvili, 1983).

Uznadze (2008) conducted an experiment using hypnotic sleep. After inducing a hypnotic sleep in the subjects, they were asked to hold pairs of different-sized spheres. This is the stage, which Uznadze called “the set experiment”, where he would “fixate the set” in the subjects, which would cause the biased perception, i.e illusion. The subjects then were told to forget everything before waking up from sleep. The illusion somehow still persisted and subjects, in the waking state, perceived spheres of identical size to be different (Nadirashvili, 1983).

From the aforementioned experiment, it was concluded that by fixating the set in the subjects, a particular inner condition is formed, which is not immediately present in the consciousness, as there is no consciousness in the hypnotic sleep (and therefore, no expectation to be disappointed), yet it persists and influences the conscious actions, such as deciding which sphere is larger. Such definition resonates well with Allport’s definition of attitude:

“a mental and neural state of readiness, organized through experience, exerting a directive and dynamic influence upon the individual’s response to all objects and situations with which it is related.” (Allport, 1935, p. 810)

Here, a mental and neural state of readiness, of course, doesn’t necessarily mean a conscious state, nor does it completely dismiss the influence of the conscious processes. At the same time, it is a state of readiness for any context, not constrained in social domain as one would expect from the term “attitude”.

4 Set Between Big and Small Theories

It is important to see how Uznadze’s experiments tackle the issue. The notion of set doesn’t simply aim to explain a particular phenomenon like Charpentier’s illusion. It is a theory that attempts to explain the general functioning of a human being as a whole. A theory using this approach is called a big (or general) theory. This is something that was often outside of the scope of the majority of research made in the field of psychology. There has seldom been a unified theory that would explain both specific peculiarities of psychological activity and human activity as a whole. This often resulted in a vast body of contradictory theories, experiments, and correlations that seemingly led to nowhere – the issue often present in small theories that focus on explaining just one particular, isolated phenomenon.

“When outlining the basis of the theory, Uznadze discussed set not as one of many psychological emergances, which should shed light on some psychological phenomena, but as the basis of human activity, which serves as a mediator between the human and the environment, moderating their interaction, determining human behavior, allowing it to be conducted purposively.” (Nadirashvili, 1983, p. 41)

Theory of set, in this regard, falls in the same category as, for example, psychoanalysis, gestalt psychology, field theory, etc. Although no theory, big or small, is safe from inconsistencies and contradictions, the unified approach dominant in big theories provides a very helpful foundation that is less cluttered with implicit preconceptions and presuppositions yet to be put under question. This foundation ensures that less epistemological harm is done. Wurtzburg’s school is a clear example of such harm.

In Wurtzburg’s school of psychology, experimental studies of attitude took a rather subjectivistic and psychologistic turn (Nadirashvili, 1983). That is to say, the accent was made not on the fact of physical, motor functions but on the conscious organization of the subject. In every experiment conducted in the context of perception, memory, reasoning, volition, etc. a great deal of attention was given to subjects’ inner state of readiness, as they assess the problem they have to solve.

Allport (1935) claims that the study of attitude in Germany had a certain methodological flaw, which hindered the scientific study of attitude. In Wurtzburg, the unified notion of attitude had dissipated, which gave rise to terms, such as: determination tendency, schema, consciousness, etc., which depicted phenomena like attitude, but were used in isolation, without anything to unify them and show a bigger picture. Besides that, they were unable to determine the locus of attitude in the psyche, for example, whether it was a conscious or unconscious process.

Although Allport’s primary concern with the attitude was in the context of social psychology, he was quite aware of its crucial role in general psychic life; Arguably due to the fact that, by its nature, attitude is unconscious. It often exerts its force without the individual realizing it.

According to Allport, the notion of attitude was first attributed to the domain of unconscious psychological activity by Freud, while also stressing its fundamental importance in psychology. According to Freud, this unconscious constitutes the energetic reservoir of psychic life and its content can only be brought to consciousness with a specific form of analysis of the psyche. It is thanks to psychoanalysis that the unconscious found its place in psychology, art, cultureal studies and social sciences in general. Allport claims, that without rigorous experimental work, the concept of attitude wouldn’t exist in psychology, but without psychoanalytic work, this concept wouldn’t have a long lifespan and fruitfulness in the field of psychology. It, certainly, for one, wouldn’t have become the central concept in social psychology (Nadirashvili, 1983).

Uznadze’s inspiration derived from Allport’s work on attitude and Levin’s field theory as the nature of set started revealing its complexity, distancing him from simple mechanistic explanations.

We could argue, that the reason other explanations of Charpentier’s illusion, as well as Wurtzburg’s research, fell short is that all of them were constructed to explain a rather too specific event. By doing so, great many aspects of human mind and behavior were simply (perhaps accidentally) ignored, rendering them inaccurate.

5 Conditions of Set Formation

Now that we are aware of the basic outline of the set, we should discuss how it comes to be. When discussing the psychic activity of a human being in relation to the environment, we assume that the behavior is purposive, i.e it serves a purpose, insofar as it is driven by inner forces, the need, that direct the actions of the individual towards the object which can gratify it. This ultimately means adapting to the environment or changing it in order to reach gratification. Changing the environment is stressed because the need on its own cannot be gratified if a particular situation is not provided, where fulfilling it is possible.

The need and the situation are what Uznadze distinguished as “the fundamental factors that give rise to any behavior and, therefore, set which precedes this behavior” (Uznadze, 2008, p. 57).

Nadirashvili (1983) provided an additional factor, operational capacity, which stresses an individual’s ability to perform gratifying tasks.

5.1 Subjective Factor: Need

The activity of a human organism can be explained on different levels. Since the psychology of set concerns itself with human activity as a whole in relation to the environment, the need is understood in its general sense, not only as instinctual, social, functional or theoretical.

“The need can be described as any state of a psycho-physical organism, which requires a change of environment, as it is provided with the necessary impulses for activity.” (Uznadze, 2008)

It is important to note, however, that the need provides the organism with necessary impulses to adapt to or change the environment, but it does not organize them, in a sense that the need is only a (more or less primitive) tendency that cannot integrate the necessary impulses with the reflected environment (situation) to guarantee the correct usage of psycho-physical resources.

Nadirashvili (1983) argues that the description of need as “any state” is rather vague and formulated the “experience of lack” that gives rise to impulses for activity. The latter notion was commonly used as the causing factor of need in psychology. The lack can be biological, as a defficiency of certain chemicals in the organism, or psychological, as, for example, a lack of social recognition but it is often the case that the need can only provide necessary impulses when the lack is experienced by the individual and it is not merely objectively present. The objective presence of a lack on a physical level can be regulated by the organism automatically thorugh, for example digestive, endocrinal or neural systems, but when a complex task is necessary to deal with the lack – thought and behavior – it must be experienced. The physical or psychological lack therefore must be reflected in the psyche (consciously or unconsciously) so that the impulses are given which are then used in the behavior.

In theory of set, the origin of need is within the individual. Uznadze (2008) is opposed to the idea that the need can arise from the external source, as is the case in Kurt Lewin’s notion of “quasineed” (see Lewin, 1951). If an object is presented to an individual that suddenly seems “alluring” to him or her, this means that there was a need for it in the individual to begin with. What varies is the intensity of need, which increases if the situation corresponds to it. The need is to be understood as a condition of an individual, which is expressed through yearning, tendency towards objects as “… it makes ground for psychic activity” (Nadirashvili, 1983, p. 208).

There are two basic types of need – substantial and functional (Uznadze, 2008). The former implies a need that can be gratified by a substance. For example, hunger can be sated by food, therefore a need for food is a substantial need. The functional need implies an organism’s yearning for activity in itself. A child’s need to play games or a musician’s need to play an instrument is often solely driven by the desire of engaging in those very activities for their own sake.

Uznadze (2008) claims that there are more beyond the basic types of needs, such as a “purely human” theoretical need. It arises when the direct act of gratification is impeded and the task at hand becomes the object of observation. In this sense, Uznadze discusses theoretical need as the development or complication of substantial need. Nadirashvili (1983) further notes that people develop certain needs based on social and cultural values. All these “higher” processes are mediated by objectification which I will explain in later chapters.

5.2 Objective Factor: Situation

When we talk about situation in set psychology, we have in mind the relevant part of the environment that makes gratification of the need possible. A need on its own can not be satisfied without the object given in the environment and the need becomes individually “defined” when it can be gratified through a certain situation.

“When there are no respective situations for individual’s needs, the tendencies towards activities that are contained in those needs remain in a passive, inactive state.” (Nadirashvili, 1983, p. 210)

While the need incorporates an impetus, the organism has no way of knowing what kind of activity must be conducted in order to satisfy it, unless the situation – which not only distinguishes future activity – gives the need a discrete, individual form.

Moreover, in order for the behavior to be purposive, the situation and need have to meaningfully coincide. A hungry person must be provided with food as a situation and not with, for example, kitchen utensils.

5.3 Operational Capacity

“The problem of purposive behavior implies the discovery of the mechanism that allows the individual to put all inner forces in service to this behavior.” (Nadirashvili, 1983, p. 218)

An individual can conduct a behavior that doesn’t lead to the gratification of his need. In this case, the behavior lacks purposiveness. For example, one might intend to jump over a hole in the ground but fall in it because he did not jump hard enough. For the behavior to be purposive (to successfully jump over the hole), it, therefore, should not only have a relevant need and situation, but also an ability to utilize the right capabilities (in this case, leg strength).

The set – the readiness to act – can only be formed with the presence of all three factors: need, situation, and operational capacity. The need on its own will not compel an individual to act if there is no objective context where gratification is possible. A situation alone cannot incite a desire as the need for it should already be present in the individual. With the need and situation the set will not arise insofar as the future behavior is imprinted as a “sketch” within it, which determines if there are right operational capacities that can cause a purposive behavior – the one that ends with gratification.

6 Types of Set

Given all three factors discussed above, a set is formed that gives rise to a purposive behavior and only the latter (not the set) can actually be observed. Now we have to see how and in what forms the set is conceived.

6.1 Fixed Set

In chapter 3 we mentioned Uznadze’s studies, where he would fixate the set in test subjects in the “experimental” phase. This was the exposure of pressure on a hand or giving subjects spherical objects on serveral occasions. This was followed by a “critical” phase, where the effects of the newly fixated set were observed. It would therefore seem that the repetitive exposure to stimuli plays a significant role in forming the set. In fact, just one or two exposures are often not enough for participants to make them perceive final equal pairs of stimuli to be different (Uznadze, 2008).

When we encounter familiar situations, our readiness to act is well-formed. That is to say, we make quick decisions, our behavior is distinct and efficient as we know (consciously or unconsciously) what to do and how to do it. That is because we have been in similar situations many times and more often we find ourselves in them, the easier it becomes for us to actualize our readiness to act, which provides us with more concise “schemas” of behavior.

“Suppose that in a certain situation I have developed a set that has played its role by giving an appropriate direction to behavior. But what happens to it after that? Does it disappear without any trace, as if it never existed, or does it somehow continue to exist, retaining the ability to influence behavior again? Since set is a modification of the subject as a unity, it is obvious that after fulfilling its role it must immediately cede its place to another set, that is, it should disappear. But this does not mean that it must cease to exist once and for all and in its entirety. On the contrary, when the subject lands in the same situation, he should develop the set in question much more easily than if he were in a completely new situation that required creating a fundamentally new set. We can safely say that a set, once created, is not lost, the subject retains it in the form of readiness for reactualization in the event that the same conditions recur.” (Uznadze, 2009, p. 80)

This is what characterizes a fixed set – an ability to remain in “the readiness for reactualization”. We could argue that what comprises a great deal of human personality is in fact a vast multitude of fixed sets, acquired through experience or genetic inheritance. It is no wonder that in set psychology there is a term called “dispositional set” that is akin to a personality trait and experience.

In Uznadze’s experiments, the repeated exposures played a crucial role. The set would not have had a distinct influence on the perception of equal objects or pressure on hands otherwise. This leads us to think that the category of fixed set encompases within itself a spectrum. That is to say, fixed sets will differ by a) how easily they can become fixed and b) how strong their readiness for actualization is.

The more often the set arises, the greater the readiness for actualization becomes. Apart from repetition, a certain situation can leave a powerful impression on the subject, so much so that even one occurance of this situation can be enough to make the set extremely fixed. Consequently, this often leads the subject to incorrectly reflect the newer situation. Instead of forming a new set, or utilizing a corresponding fixed set, the previous extremely fixed set becomes actualized and henceforth the subject becomes the victim of an illusion. This concept opens up possibilities of exploring psychological trauma in novel ways but this is beyond the scope of our discussion. We are interested on how the fixed set explains Uznadzde’s experiments.

“Therefore, because of frequent repetition or significant personal importance, a certain set may be as easily aroused as a habitual one that is easily actualized even under the influence of an unrelated stimulus that impedes the appearance of the appropriate set. This may be called a fixed set.” (Uznadze, 2009, p. 80)

Indeed, this is what happens in Uznadze’s experiments, where upon many repetitions, the perception of two different stimuli is so strongly fixed that later, even the two identical stimuli are perceived to be different.

It is important to note that although the purpose of set is subject’s adaptation to reality, it is not always necessary to fully reflect the external reailty. Within the set that constitutes impulsive behavior the individual reflects objects and his behavior to an extent that is important and enough for the corresponding behavior of this set. When interacting with reality, an individual comes in contact with a vast variety of objects, each of them unique. Despite that, those objects have similarities based on which human psyche tends to simplify and categorize those objects in an assimilative manner. This ensures purposive behavior without extra psychological strain (Nadirashvili, 1985). This is precisely what we see in Uznadze’s experiments, where the fixed set of perceiving different objects affects the perception of same objects – an “assimilative illusion” takes place.

6.2 Situational Set

What should we make of the set that is never retained in the subject and which simply disappears after serving its purpose as the corresponding situation never presents itself again?

“At the initial conception, the set does not simply form in a complete form, but rather it is usually in the undifferentiated state that lacks individualized nature.” (Uznadze, 2008, p. 69)

When we are dealing with the set at its earliest stage of formation it is rather difficult to observe and study because it is diffused, and the behavior it produces is less apparent. It is important to note that if the set is not differentiated, it will not produce an organized behavior, let alone an observable one because the factors of set are not yet differentiated and they are not corresponding to each other (Nadareishvili, 2016). This is why, in unfamiliar situations, people tend to become clumsy and awkward. First and foremost, then, the factors of set must be differentiated, which is difficult in an unfamiliar situation and requires a bit more effort.

We are therefore lead to believe that in Uznadze’s research discussed in chapter 3, the set experiment does not only require the fixation of set but also its differentiation (Uznadze, 2008). Only after the set and the behavior it organizes become defined, we can make conclusions.

Once a completely new set is differentiated it serves its purpose and recedes if the situation passes and never recurs. Precisely because of that, it is called a situational set. It forms when an individual is presented with a completely new and unfamiliar situation.

There is no concrete general measurement on how many repetitions a set requires to become fixed. It largely depends on both the individual and the context in which he acts. It is even possible for the fixation to not occur at all, despite the amount of stimuli given, while in some subjects, even one strong impression is enough. In this case, the subject himself plays a crucial role, as a unitary living being. In experiments of Uznadze (2009), for example, it took 15 repetitions to successfully fixate the set in the majority of subjects.

In conclusion, when we speak about the formation of set, at the first stage we have a diffused set which has yet to be differentiated i.e to develop a distinct form. Through the help of repetition or personal significance of the situation, event or stimulus, the set starts to become differentiated. It either becomes a situational set that serves its purpose one time and disappears as the situation never presents itself again, or it becomes fixed as it acquires an ability to retain itself within the subject and to have readiness for actualization, provided that the subject encounters the same situation.

6.3 Intricacies of Fixed and Situational Set

There’s a complex interrelation between different sets within the individual which becomes apparent when we observe assimilative and contrast illusions that were present in experiments regarding object size. It also gives us insight on how the set disappears, allowing a new set to replace it.

“A test subject is repeatedly (ten to fifteen times) handed, and asked to compare, two objects that differ only in volume: a small one in the right hand, a large one in the left. When the test subject participates seriously in this experiment, he develops, under the effect of our instructions, a need to accomplish the task assigned to him (the subjective factor of set). The proffered objects (the objective factor) act on the subject who has this need by producing a specific effect (the set), on the basis of which a correct assessment is made of the relative volumes of these objects. Consequently, after each hand-off, the test subject develops a set (“big one on the left, little one on the right”). As a result of multiple repetitions this set becomes so habitual that in each subsequent experiment it is actualized even before the proffered objects exert the appropriate effect. After that, the test subject is handed, and asked to compare, objects with equal rather than different volumes (the critical experiment). What occurs in this instance? If objects of not very different volumes were used in the experiments designed to create a certain set, then the habitual set remains in effect, and the assessment of the equal objects is based on that: the right-hand object seems smaller to the test subject than the left-hand one. But if objects of starkly different volumes are used in the set experiments, when equal objects are presented in the critical experiment, the old set cannot manifest itself because of its gross discordance with the objective factor, and a new set must take its place. The experiments prove that everything occurs just that way.” (Uznadze, 2009, p. 81)

In the critical experiments two different cases emerged. When the difference between two objects is not so big in the set experiment, the previous set still has an effect in the critical experiment, when they are handed equal objects – “the big one is on the left, little one on the right”. Here we have an assimilative illusion. When the difference between objects is far too big in the set experiment, the opposite happens when they are given equal objects – “the big one on the right, little one on the left”. The latter is a contrast illusion. Why would the newer set in the second case not conform to the previous set and instead be a direct opposite of it? Uznadze claims that in both cases the set developed in the set experiments play a significant role. According to Nadirashvili (1985), when the set meaningfully corresponds but at the same time signifficantly differs from objects and events, a contrast illusion takes effect whereby contrasting feeling further exaggerates the difference which exists between the individual’s set and events of the reality. The contrasting experience – due to the counteraction of the exaggerated information on the inappropriate set – speeds up the deterrioration of the set that is inappropriate for the given situation. This way, conditions form so that the individual can change according to the external reality. The contrasting feeling that derives from the set allows the individual to dispose of the inappropriate set and give ground for a new relevant set.

It is therefore logical to claim that fixed sets often play a mediating role between other sets and their behaviors (Nadirashvili, 1985). A dispositional set, for example, plays a significant role when a situational set is formd in an unfamiliar situation. Here, a dispositional set on its own might not correspond to the particular environment due to its general nature, therefore it influences the structure of the situational set that is being formed (Nadareishvili, 2016). It is worth noting, that volition plays a significant role in this process, which will be adressed in Chapter 7.2.

Furthermore, it is argued that situational set organizes the structure of a dispositional set (Nadareishvili, 2022). That is to say, a dispositional set (which is a certain type of fixed set) does not simply recede, but rather has its components modified by a situational set to better suit the demands of the newer situation.

In conclusion, we can see that human activity, in terms of set, cannot simply be explained by different sets switching places with one another, or ensuring the destruction of one on the basis of the other’s formation. The existing sets can modify each other’s structural components (for an in-depth overview, see Nadareishvili, 2022).

7 Two Levels of Activity

As the theory of set expanded, it became apparent that the elaborate nature of the human’s psychic activity, such as social and volitional activity, cannot simply be explained with set that arises from need and objective reality. It became necessary to explore sets that not only reflect the need and objects from external reality but also social demands and values – all of which happen on a higher level of activity (Nadirashvili, 1985).

In the early stages of the set theory, a more primitive level of human activity was considered. Later the notion of objectification was introduced to distinguish two forms of sets and, in general, two levels of activities.

7.1 The First Level

On the first level, we encounter an impulsive behavior. The behavior is, in this case, largely directed by set. An individual’s relation to the environment is mostly fragmented and practical – purely for the sake of “consumption”. The individual only interacts with the parts of the reality that is related to his need.

“During impulsive behavior, be it eating or a different form of consumption, an individual chooses, on the basis of his set, the agents of activity. He chooses food on the table that looks the most attractive to him. If this procedure happens on an official feast, he impulsively, through set, follows all the rules and etiquette which is socially reinforced and which he has developed from experience. For an individual who is well versed in this domain, reflecting necessary objects, giving direction to physical forces towards them and obeying the etiquette of the feast does not require special attention and volition”. (Nadirashvili, 1985, pp. 33–34)

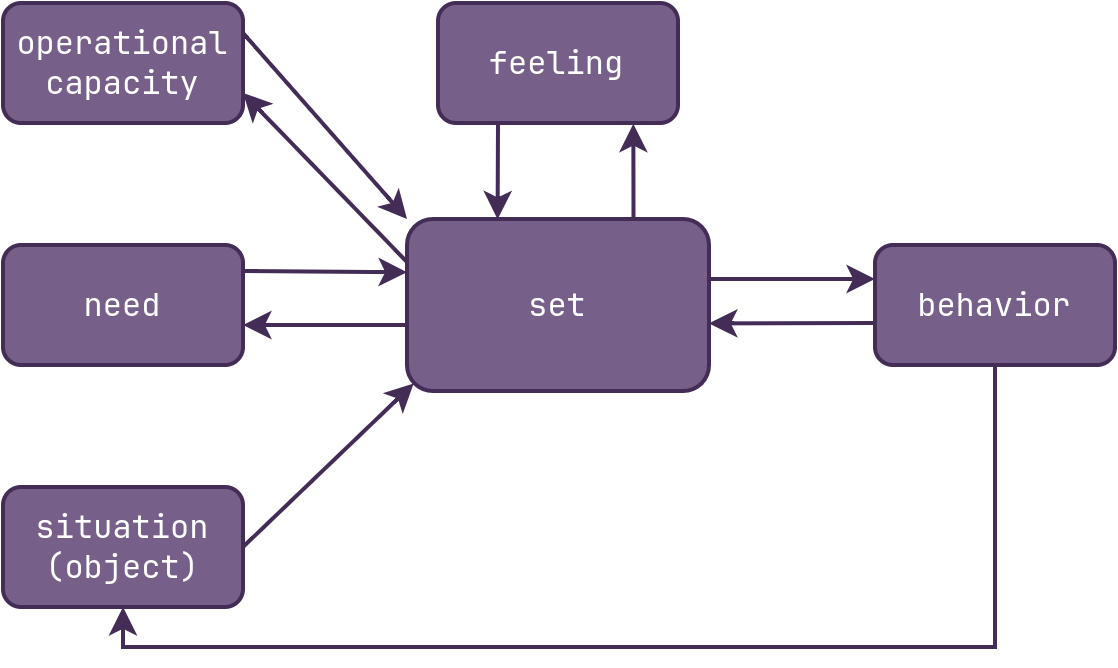

If we were to display the first level of activity on a chart, it would look like this:

Structure of the first level of psychic activity (translated from Nadirashvili, 1983).

The set is directly related to all of its three factors, as well as the feeling – the experience that comes from external reality – and behavior. At the same time, it mediates all of them. Only the set’s relation with the object is not direct from both directions. The object is directly reflected in the set, but the set can only influence the object through behavior. At the same time, the object’s interaction with the set is not isolated because the corresponding need and operational capacity must be active.

A basic example of object’s direct reflection in set would be the separation of background and foreground in perception. The objects necessary for need gratification are differentiated from the rest of the environment, towards which an individual has specific reactions. This particularity of perception is due to the set. Objects related to the active set appear to be more distinguished and attractive. Hungrier a mouse is, the more attractive to it seems the piece of cheese and less noticeable – the mousetrap which holds this cheese (Nadirashvili, 1985).

During impulsive behavior, conscious processes are less involved as the relevant part of the environment is already reflected in the set. It is when the impulsive behavior is impeded (i.e fails to be purposive) that it becomes necessary to mobilize consciousness. This is where the objectification plays a crucial role.

Objectification is a mechanism that allows the individual to once more and far thoroughly reflect the environment (be it physical, social or theoretical) which, during impulsive behavior, has become an obstacle to need gratification. It might be seen as a “switch” that, as conscious resources become more necessary, moves psychic activity to the second level where it becomes possible to find a way to continue previous behavior or form a new behavior that will not be impeded. This requires conscious reasoning in particular.

The two levels of activities are not a division between the conscious and unconscious processes, as consciousness is involved on both levels to some degree. The experience of an object, which we encapsulated as “feeling” in the chart above is what Uznadze referred to as “contents of consciousness”. It is a stream of experiences that create a foundation for future operations in behavior. These experiences, feelings, contents are, however, fragmented on the first level of activity and therefore do not direct the behavior on their own as it is the set that contains a “general strategy for behavior” (Nadirashvili, 1985, p. 54) and gives unity to these contents of consciousness on basis of which impulsive behavior takes place.

7.2 The Second Level

On the second level of activity an individual deals with problems that cannot be solved on the first level. Simply because such problems cannot even be noticed on a more primitive level.

Impulsive behavior, as we know, required several factors and when one of them falls out of place – for example, when the situation no longer can gratify the need – the impulsive behavior comes to a halt.

“Turns out, that a human can stop his impulsive activity by taking out one of its factors from the context of behavior. He does so by directing attention to, and therefore through objectification of, one of the factors of behavior… Once he starts contemplating about the functionality of his behavior’s components, his impulsive behavior is stopped.” (Nadirashvili, 1985, p. 75)

The definition of objectification we see above is not exhaustive. During impulsive behavior there is no subjectivity in the individual to speak of, in a sense that the behavior is conducted unconsciously while the individual is a mere part of the activity: the subject is lost in the behavior. He does not get to (consciously) choose his actions. Through objectification the factor of behavior causing the impediment is differentiated as an object to which a now consciously thinking individual is related as a subject, thus forming a subject-to-object relationship. In other words, the individual starts abstract reasoning about what went wrong. While physically during this moment we can only observe that impulsive behavior stops, psychologically an activity is initiated on a completely different plain. Through objectification an individual can differentiate himself from the environment and relate himself to it as a subject to an object.

Objectification as an ability is developed in humans through social interactions and it is unique to humans insofar as they are capable of communication within a complex system that is language. Thus socialization develops the ability of objectification, “…when during collective work it would become necessary to point to the object towards which the common behavior of the group was directed” (Nadirashvili, 1985, p. 76).

It is worth noting that although in this discussion we focus on objectification of an object (in the environment), other types of objectifications have also been distinguished, namely objectification of social influence and self-objectification (Nadirashvili, 1985) – all of which are beyond the scope of this article.

Despite the activities being on two different levels, the feeling of the external reality on the second level maintains the equivalency of the first level. The objects in reality are experienced to be the same on both levels, with the benefit of higher level comprehension through consciousness on the second level. This allows the individual to employ higher levels of cognitive functions to inspect the reason why the impulsive behavior was impeded and to find the solution. This also allows the individual to contemplate, in his psychic reality, all of its possibilities and potentialities. On this level, the behavior can incorporate physical, ideal, and social acts, therefore the behavior can become not only purposive, but deliberate and creative. This is the key difference in terms of behavior between two levels of activities: On the first level, the behavior is purposive, and on the second level, it is deliberate.

As mentioned above, the purpose of the activity on the second level is being able to return to the impulsive behavior on the first level. The transition back to the first level is one of the more complicated problems that is a subject of a debate to this day.

Some researchers in this field have argued that volition is always necessary for the activity to return to the first level. A research (Natadze, 1972, as cited in Nadirashvili, 1985) has shown that volition may only be required if the correct set cannot be formed due to an opposing set being too firm, which required extra conscious effort to oppose it. In other cases ideas and imaginations that arise on the basis of objectification are sufficient to form and fixate a new set.

Imagination plays a significant role on the second level. In fact, what distinguishes the sets formed on either level of activity is the nature of its factors. What constitutes impulsive behavior is a set that has real inner and outer factors: the need is truely present in the organism and there’s a real object (situation) that can gratify the need in the environment. The set that directs deliberate behavior, however, lacks this kind of reality in at least one of its factors.

Suppose that as we perform our morning routine, we prepare for work but as we reach out for a usual spot where we keep our car keys, we realize that they are not there. Up until this point, most of our activity – getting dressed, brushing teeth, having breakfast – was largely conducted by the set as all of its factors were present both within us and in the real world (we were hungry, and we had breakfast prepared), the same thing should have been true for the keys – we wanted to drive a car to work and the keys should have been at the usual spot. As the objective factor, the keys, fell out of place, and by feeling this mismatch we would initiate objectification: “Where are the car keys? I always put them here! Perhaps I left it in my coat pocket? Maybe it’s in my bag…”. With the help of reasoning, we would start looking for the keys in the places where we suspect it might be. What constitutes our set that initiates our search behavior? Well, we need to get to work (need), we are capable of driving (operational capacity) but the keys (situation) are not there! – they are imagined as possibilities of where they could be. Successfully finishing this behavior (finding the keys) will not gratify our need as we still have to get to work (therefore it is not purposive, but deliberate) but it will allow us to return to the impulsive and purposive behavior that ends with us going to work. This would also help as fixate a new set whereupon if the keys are missing again, we will (this time impulsively) without much conscious reasoning, reach into our coat pocket or a bag where we had found it previously.

Of course, the imagined factor does not have to be just the objective one. For example, a individual may through volition acquire necessary skills for a task that he wants to accomplish by practicing.

As a side note, the formation of situational set can be now described precisely. Since the situational set forms in a new, unfamiliar situation, the impulsive behavior is impeded, since the factors of set are not differenciated. This means that an individual must use volition and imagination to differenciate those factors and through deliberate behavior find means to “make himself at home”, in other words to return to purposive behavior in a (now) familiar situation.

In conclusion, what differentiates the two levels of activities is the behavior and set which constitutes it. The behavior on the first level is largely driven by the set that has its factors fully and objectively present, therefore it is impulsive. The behavior at this level is also purposive, as it ends with the gratification of need. The second level of activity becomes necessary when the impulsive behavior is impeded. The objectification allows an individual to “take a step back” and once again, albeit thoroughly, observe the cause of the impediment. Through more involved conscious processes it becomes possible to create a new set, this time with imagined factors that allows the individual to conduct deliberate behavior which serves the purpose of returning to an impulsive and purposive behavior.

8 The Reach of Set Psychology

Uznadze’s school of set psychology became the most prominent field in USSR that studied the unconscious. Interestingly enough, it withstood the pressure of falling in line with Marxist philosophy, even though it was mostly devoid of any ideology (Imedadze, 2022).

The unique and generalized approach of set psychology allows it to be applied to many fields, such as social psychology (Nadirashvili, 1983, 1985), criminal psychology (Nadareishvili & Chkheidze, 2013), abnormal psychology (Uznadze, 1977; Uznadze & Haigh, 1966) and more.

Uznadze was ambitious enough to claim that Freud’s understanding of the unconscious is flawed and the Freudian term unconscious should be replaced by the set (Uznadze & Haigh, 1966, p 213-214). His claims are not to be dismissed so easily as while psychoanalysis could vouch for its validity through success in treatment, the set psychology was able to experimentally study the unconscious and as a result founded the alternate theory of the unconscious which, to this day, lacks the attention it deserves beyond the borders of Georgia.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In A handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Worcester, MA, US: Clark University Press.

- Angelini, A. (2008). History of the unconscious in soviet russia: from its origins to the fall of the soviet union. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 89, 369–388.

- Imedadze, I. (2009). Uznadze’s scientific body of work and problems of general psychology. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 47(3), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405470301

- Imedadze, I. (2019). TBILISI 1979 date SYMPOSIUM ON THE UNCONSCIOUS – LOOKING BACK. Problems of Psychology in the 21st Century, 13, Continuous. https://doi.org/10.33225/ppc/19.13.4

- Imedadze, I. (2022). TBILISI SYMPOSIUM ON THE UNCONSCIOUS - A SHORT RETROSPECTIVE. GEORGIAN PSYCHOLOGICAL JOURNAL, (1). https://doi.org/10.52340/gpj.2022.07.13

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science: selected theoretical papers (edited by dorwin cartwright.).

- Murray, D. J., Ellis, R. R., Bandomir, C. A., & Ross, H. E. (1991). Charpentier (1891) on size-weight illusion. Perception & Psychophysics, 61 (8), 1681–1685. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03213127

- Nadareishvili, V. (2016). განწყობის დიფერენციაციის საკითხები. Დ.Უზნაძის Სამეცნიერო Შემოქმედება Და Ფსიქოლოგიის Აქტუალური Პრობლემები, 177–182.

- Nadareishvili, V. (2022). INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FIXED AND SITUATIONAL MENTAL ENTITIES. GEORGIAN PSYCHOLOGICAL JOURNAL, (1). https://doi.org/10.52340/gpj.2022.07.12

- Nadareishvili, V., & Chkheidze, T. (2013). Normative and deviant behavior in terms of D. Uznadze set theory based strain model. European Scientific Journal, 2, 542–547.

- Nadirashvili, S. (1983). განწყობის ფსიქოლოგია (Vol. 1). თბილისი: მეცნიერება.

- Nadirashvili, S. (1985). განწყობის ფსიქოლოგია (სოციალური განწყობა) (Vol. 2). თბილისი: მეცნიერება.

- Uznadze, D. (2009). The psychology of set. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 47, 67–93. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405470304

- Uznadze, Dimitri. (1977). შრომები. თბილისი: თბილისი.

- Uznadze, Dimitri. (2008). განწყობის ფსიქოლოგიის ექსპერიმენტული საფუძვლები. საქართველოს მაცნე.

- Uznadze, Dimitri, & Haigh, B. (1966). The psychology of set. New York: Consultants Bureau.